I am at a-loss to account for the received maxim, that ‘in good wine there is truth;’ and should no more expect happiness in a full bowl, than chastity in a bar of a tavern.

I am at a-loss to account for the received maxim, that ‘in good wine there is truth;’ and should no more expect happiness in a full bowl, than chastity in a bar of a tavern.

Connoisseur (London), October 30, 1755

Although many today think of the Temperance Movement as an early 20th-century initiative, throughout history some members of society have pushed for greater moderation or abstinence in terms of alcoholic beverage consumption. In ancient Greece and Rome, it was considered crude and unsophisticated to become inebriated. In the same vein, Cyrus Redding, author of Every Man his Own Butler (London, 1839), tells us that “the chief thing in the art of drinking wine, is to keep within those salutory limits which mark the beneficial from the pernicious.” Distilled spirits such as gin and whiskey became cheaper and more widely available after the early 1700s, leading to greater alcoholism among those who had traditionally drunk beer or ale, which were lower in alcohol content. Some temperance groups even praised the latter as healthier alternatives to spirits.

During the 1800s religious sermons, parades, and articles regarding temperance proliferated, with many lessons on the subject being taught through story-telling. Children and adults were exposed in subtle ways to the idea of temperance or moderation in all things via games and, in some cases, objects placed around the home. In public spaces such as churches and meeting halls, the concept of complete abstinence from alcohol was often voiced more loudly.

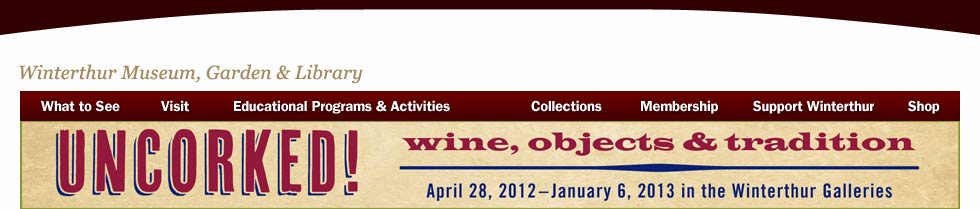

Punch bowl

Probably London, England; 1760–70

Earthenware (delftware)

Inscribed “My wife drinks Tea / And I’le drink punch”

Gift of Mrs. Nancy du Pont Reynolds 2003.22.30

Perhaps a special commission, this punch bowl bears a rare inscription indicating that drinking habits were  sometimes separated along gender lines. More commonly, such bowls bear simple drinking-related phrases, such as “One bowl more and then…,” or inscriptions expressing wishes for success in trade or military endeavors.

sometimes separated along gender lines. More commonly, such bowls bear simple drinking-related phrases, such as “One bowl more and then…,” or inscriptions expressing wishes for success in trade or military endeavors.

The Harlot at Her Dwelling in Drury Lane

The Harlot at Her Dwelling in Drury Lane

William Hogarth

London, England; 1744–1849

Ink, watercolor on wove paper

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Irvin G. Schorsch, Jr. 1985.156.1

The first edition of Hogarth’s Harlot’s Progress was released in 1732, and the popular series was reissued many times. In this scene, the harlot’s maid fills a teapot with alcohol, presumably to disguise the beverage. Among other symbolic objects, the cracked punch bowl references lost virtue.

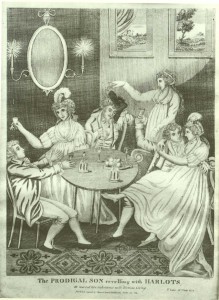

The Prodigal Son Revelling with Harlots

Amos Doolittle

Cheshire, Connecticut; 1814

Line etching with burin work on wove paper

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1957.619.2

The biblical parable of the Prodigal Son tells of a young man who leaves home and lives a life of excess until he loses everything. In the print shown here, the son and his companions enjoy wine served in elegant cut-glass decanters and wineglasses.

Virtue and Vice, Sobriety and Drunkenness

Virtue and Vice, Sobriety and Drunkenness

Thomas Birch

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1815–30

Ink wash on paper

Museum purchase 1967.131

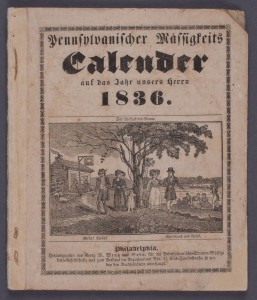

Pennsylvania Temperance Calendar (Almanac)

Georg W. Menz & Son (publisher)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; dated 1836

Inscribed “Pennsylvanisher Massigkeits Calender auf das Jahr unsers Herrn 1836”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.1711

The front cover of the 34-page German almanac bears a somewhat crudely executed version of the larger scene by Birch. In the distance is the Schuylkill River and Water Works; at mid-distance men drink on the porch of a rural tavern. In the foreground (left) a poor family stands under leafless branches, nearer to the tavern. Under the healthy side of the tree we see a well-dressed man and his wife and a distant group of people picnicking. The scene on the almanac cover is titled “Der Massigkeits-Baum” (The Temperance Tree).

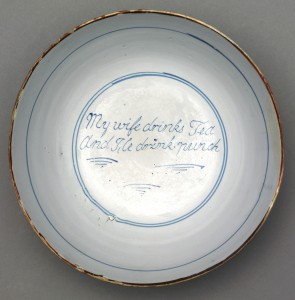

The DRUNKARD’S PROGRESS, OR THE DIRECT ROAD TO POVERTY, WRETCHEDNESS & RUIN

John Warner Barber

New Haven, Connecticut; 1867

New Haven, Connecticut; 1867

Ink on wove paper

Museum purchase 1967.123

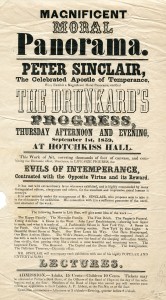

Advertisement for “Moral Panorama . . . THE DRUNKARD’S/ PROGRESS”

Waterbury, Connecticut; dated September 1, 1859

Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library Col. 214 77×135

The Drunkard’s Progress, inspired by earlier series portraying the prodigal son, illustrates the road to ruin resulting from alcohol consumption. One version of the story can be followed in the four-part print shown here. As can be seen on the poster nearby, this subject was presented to the public in other forms as well. Visitors are invited to experience a “Work of Art, covering thousands of feet of canvass” with life-size figures illustrating scenes such as “The Happy Family,” “The First Drink” and “Our Hero Loses his Way.” These are presented by Peter Sinclair, the “Celebrated Apostle of Temperance” who offered lectures to accompany the exhibition. Sinclair was a member of the “Band of Hope,” a temperance society in Waterbury, Connecticut, that sometimes met at the town’s Hotchkiss Hall.

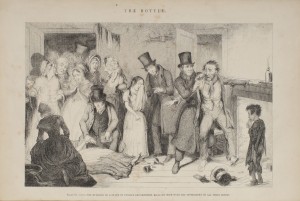

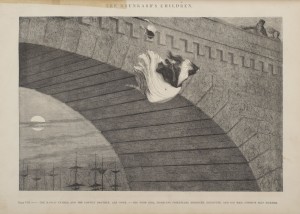

The Bottle. In Eight Plates; with The Drunkard’s Children. A Sequel To The Bottle. In Eight Plates

The Bottle. In Eight Plates; with The Drunkard’s Children. A Sequel To The Bottle. In Eight Plates

George Cruikshank (illustrator)

London,England: D. Brogue, 1848

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NC1479 C95b F

(Shown here) “THE BOTTLE BROUGHT OUT FOR THE FIRST  TIME…,” “THE HUSBAND IN A STATE OF FURIOUS DRUNKENNESS KILLS HIS WIFE,” “THE POOR GIRL . . . COMMITS SELF MURDER”

TIME…,” “THE HUSBAND IN A STATE OF FURIOUS DRUNKENNESS KILLS HIS WIFE,” “THE POOR GIRL . . . COMMITS SELF MURDER”

In this sad and internationally published story, a dark shadow falls on a happy family when the father decides to take to drink. The couple soon loses their household belongings because of the now-unemployed  father’s weakness. Depressed, he becomes violent, murders his wife by clubbing her with a bottle, and is imprisoned. In the sequel, The Drunkard’s Children, the cycle continues with the children taking to drink and circulating through a series of bars and gin palaces. Illness, jail, and deportation are the fates of the son. The alcohol-addicted daughter, unable to bear her life any longer, leaps to her death from a bridge.

father’s weakness. Depressed, he becomes violent, murders his wife by clubbing her with a bottle, and is imprisoned. In the sequel, The Drunkard’s Children, the cycle continues with the children taking to drink and circulating through a series of bars and gin palaces. Illness, jail, and deportation are the fates of the son. The alcohol-addicted daughter, unable to bear her life any longer, leaps to her death from a bridge.

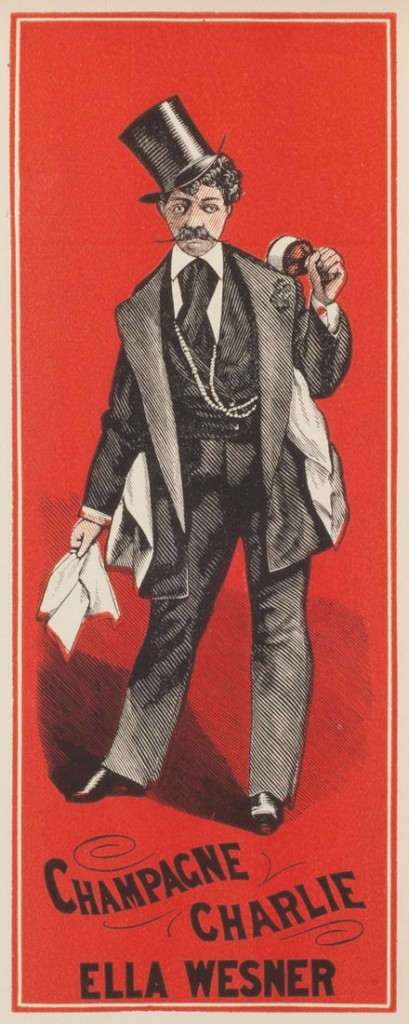

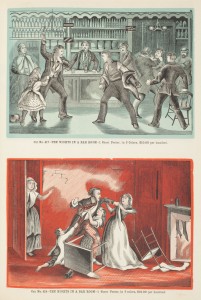

Specimens of Theatrical Cuts: Being Fac-similes, in Miniature, of Poster Cuts

Specimens of Theatrical Cuts: Being Fac-similes, in Miniature, of Poster Cuts

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Ledger Job Printing, 1872 or 1878

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NC1840 P97a TC*

Among the thousands of images that could be ordered from this catalogue as full-size theater advertisements are several illustrating popular temperance plays. Shown here are scenes from Timothy Shay Arthur’s 1854 novel (later a play) Ten Nights in a Bar-Room. The story tells of a miller who decides to open a tavern. Over time, he, his family, and the people of the town deteriorate because oftheill-effects of alcohol. This popular story was reproduced into the 20th centuryas plays and at least two movies.

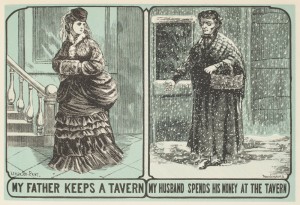

The same concept of taverns as a detriment to society is illustrated in the double-view available to be ordered from the same catalogue. These images, comparing a well-dressed wealthy young woman to a ragged and poverty-stricken one, are poignantly titled “MY FATHER KEEPS A TAVERN” and “MY HUSBAND SPENDS HIS MONEY

The same concept of taverns as a detriment to society is illustrated in the double-view available to be ordered from the same catalogue. These images, comparing a well-dressed wealthy young woman to a ragged and poverty-stricken one, are poignantly titled “MY FATHER KEEPS A TAVERN” and “MY HUSBAND SPENDS HIS MONEY  AT THE TAVERN.”

AT THE TAVERN.”

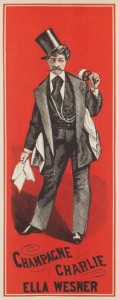

The dark portrayal at the right shows the fictitious “man-about-town” Champagne Charlie as a drunkard, as played by the famous actress Ella Wesner. This view may have appealed to Temperance Movement supporters such as the Salvation Army, which adapted the Champagne Charlie song into their own “Bless His Name He Sets Me Free.” (To see Charlie portrayed in a more optimistic light, see Wines by Type.)

Plaque with Temperance Arms

Plaque with Temperance Arms

Probably Newcastle on Tyne, Sunderland, England; 1820–50

Earthenware (lusterware)

Promised gift of Wendy Cooper

So-called Temperance Arms motifs were created in a variety of forms to represent specific societies as well as a more widespread social statement. Plaques of this general type were produced in England for domestic and foreign markets.

Temperance banner

Probably United States; about 1850

Cotton, silk, paint

Inscribed “Tempranc with pinions widely spread, / Flies through the earth at heavens command. / And blessings by her influence shed, / Charter her rule in every land.”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.7815

The Temperance Movement already had a scattered foothold inAmericawhen Dr. Benjamin Rush published his influential 1784 article “An Inquiry into the Effects of Spiritous Liquors on the Human Body and the Mind.” The banner shown here is of unknown origin but may resemble those seen by Charles Dickens in Cincinnati when hewitnessed “a great Temperance Convention” that paraded below his hotel window:

It comprised several thousand men . . . and was marshalled by officers on horseback, who cantered briskly up and down the line, with scarves and ribbons of bright colours fluttering out behind them gaily. There were bands of music too, and banners out of number . . . The banners were very well-painted, and flaunted down the street famously.

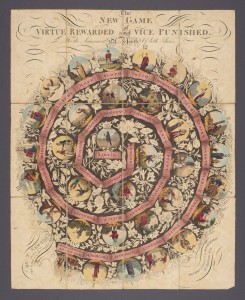

The NEW GAME of VIRTUE REWARDED and VICE PUNISHED

William Darton (publisher)

London, England; dated 1818

Ink, watercolor on cloth and paper

Museum purchase 1955.50.12a,b

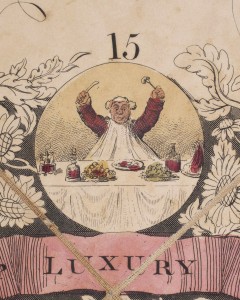

This popular board game was available for purchase in Philadelphia at “S. HART’S FANCY STATIONARY And Print Store, No. 65, S. Third Street.” The image of “LUXURY” showing a cheerful man with wine and elegant food might be thought to  portray a “good thing,” but it fits into a “negative” slot in the game, which shows good alternating with bad qualities. This game was preceded by others also intended to teach morality to children, including John Harris’s 1804 New Game of Emulation, which was “Designed for the Amusement of Youth of Both Sexes and Calculated to Inspire their Minds with an Abhorrence of Vice and a Love of Virtue.” Many such games were mounted on sturdy cloth backings and folded to be sold in thin, pressboard cases.

portray a “good thing,” but it fits into a “negative” slot in the game, which shows good alternating with bad qualities. This game was preceded by others also intended to teach morality to children, including John Harris’s 1804 New Game of Emulation, which was “Designed for the Amusement of Youth of Both Sexes and Calculated to Inspire their Minds with an Abhorrence of Vice and a Love of Virtue.” Many such games were mounted on sturdy cloth backings and folded to be sold in thin, pressboard cases.