By at least the 8th century BC, Greeks were trading with southern Italy, and soon wine became a part of many religious and secular celebrations. Large, open vessels called kraters, dedicated to Dionysus (Bacchus), were a central focus at such events and held a strong wine that was made drinkable with the addition of water. When kraters and smaller wine vessels were excavated in later eras, they inspired the production of a wide variety of sculpture and other wares for the homes and gardens of wealthy Europeans and Americans. Like the ancient vessel forms, some classical wine-related terms also survive today. The word symposium, for example, originally referred to drinking parties that might include intellectual conversation, music, and romance.

Coming to Terms with Classical Wine Vessels

- Amphora—Means “carried on both sides.” Such vessels commonly feature two handles, a narrow neck that flares at the rim, and a pointed lower portion to the belly, sometimes without a foot.

- Askos—A closed vessel related to ancient animal-skin bags for transporting or storing liquids. They typically feature a rounded belly with an off-center narrow neck and an upward-looping handle.

- Hydria—Originated in Greece. They were used to carry water and feature a wide, rounded belly and several handles: the horizontal pair is for lifting and the vertical handle at the back facilitates pouring.

- Kantharos—A wide-bellied, deep drinking vessel typically featuring two large, opposing vertical handles that continue high above the rim. The base can be short or tall, depending on date and place of origin.

- Krater—Derived from keránnymi, meaning “to mix.” Kraters typically are large; were used for mixing wine and water; and played a central role in ancient wine rituals. Drinks were served by dipping containers or cups into the krater. Some feature an inner container for wine or water and an outer one for chilled water or snow.

Print portraying Sir William Hamilton and members of the Society of Dilettanti

Print portraying Sir William Hamilton and members of the Society of Dilettanti

William Say, after Sir Joshua Reynolds

London, England; about 1830

Ink on paper

Gift of Frank Henry Sommer, Ph.D. 2004.68.34

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a dilettante as “a lover of the fine arts; originally, one who cultivates them for the love of them rather than professionally.” The famous London Society of Dilettanti first met in 1732 with the intent of studying ancient Greek and Roman artwork. The group also encouraged modern reproductions such as the neoclassical ceramics made by Josiah Wedgwood of Staffordshire. In the scene shown here, Sir William Hamilton discusses a red-figure wine vessel that appears in the famous catalogue of his collection. (For another print portraying the Dilettanti, see Clubs, Friendship & Well-Wishing.)

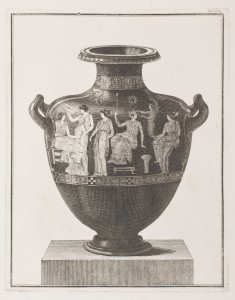

Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques, et Romaines Tirées du Cabinet du M. William Hamilton, vol. 1, pl. 30.181 (sic)

Pierre-François Hugues D’Hancarville

Naples, Italy: W. Hamilton, 1766/67

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NK4624 H22co PF

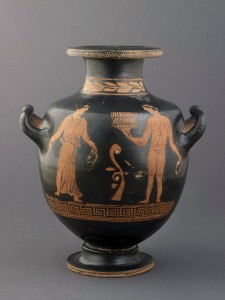

Hydria (jug)

Probably Athens, Greece; 380–360 BC

Earthenware (redware)

Bequest of Oliver I. Shoemaker 2008.11.39

Sir William Hamilton served as a Member of Parliament and was Britain’s ambassador to the court of Naples from 1764 to 1800. He was also a member of the Society of Dilettanti, a group of enthusiasts who focused on classical antiquities. Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques, et Romaines, published in English, French, and German, catalogued Hamilton’s famous collection of Greek and Roman vases and other objects. The engraved bookplate shown here shows a hydria; compare it to the ceramic example seen nearby. In ancient Greece and Rome, wine and water were combined to make the wine more palatable and to lower the alcohol content. Hydrias held water and are sometimes decorated with wine-drinking scenes.

Vase inspired by ancient amphora

Josiah Wedgwood’s Etruria factory

Staffordshire, England; 1770–80

Stoneware (black basaltes)

Gift of Lindsay Grigsby 2011.19.2

“Apollo and Muses” amphora shape vase

Josiah Wedgwood’s Etruria factory

Staffordshire, England; about 1787

Stoneware (jasperware)

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle and the Winterthur Centenary Fund 1997.14

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle and the Winterthur Centenary Fund 1997.14

Both of these Wedgwood vases are of forms inspired by ancient amphora, used for serving wine. The jasperware vase is a type shown in the 1787 Wedgwood catalogue and ordered by Philadelphia Quaker “fancy goods merchant” John Bringhurst in January 1793. Bringhurst, who appears to have ordered the vase through his English uncle and agent, physician Thomas Pole, supplied goods to the Department of State under Thomas Jefferson, to the prominent Chew family of Philadelphia, and to Martha and George Washington.

Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques, et Romaines Tirées du Cabinet du M. William Hamilton, vol. 2, pl. 39

Pierre-François Hugues D’Hancarville

Naples, Italy: W. Hamilton, 1766/67

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NK4624 H22co PF

Kantharos-form potpourri vase or pastille burner

Josiah Wedgwood’s Etruria factory

Staffordshire, England; 1805–20

Stoneware (black basaltes)

Anonymous gift to honor Leslie Greene Bowman 2000.60a-c

Sir William Hamilton’s catalogue, Antiquités, was an extremely important inspiration and reference for the reproduction of ancient vessel forms. After much of his collection was sold to the British Museum, the actual objects became available for study by artists and manufacturers.

The Greek “Apulian kantharos (Gnathia)” was originally used as a wine cup and may have inspired the design of the Wedgwood basalt pastille burner shown here. In such objects, small, dense pellets or lozenges of aromatic paste were burned to provide a pleasant scent or “perceived” medicinal benefits.

Coupes, Vases, Candélabres, Sarcophages, Trépieds, Lampes & Ornements Divers, pl. 3

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Paris, France: A. Vincent, 1905

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NK1225 P66p F

Tureen, stand, and liner

Rundell, Bridge & Rundell

London, England; 1828‒29

Gilt silver

Campbell Collection of Soup Tureens at Winterthur 1996.4.252a-d

The engraving shown here reproduces an 18th-century original by Giovanni Battista Piranesi and portrays the famous “Warwick Vase.” That vase resembles wine vessel forms and is decorated with heads associated with the Bacchanal. It was excavated in Italy, restored, and eventually purchased by the British Ambassador to Naples, Sir William Hamilton. Hamilton’s nephew, George Greville, 2nd Earl of Warwick, displayed the vase at Warwick Castle. It was also re-created in paintings, ceramics, and metalwork, including an early 20th-century pair of massive lead flower containers that Henry Francis du Pont acquired for display in the Winterthur garden.

The impressive gilt silver tureen takes its shape from the Warwick Vase but substitutes grapevine ornament for the human heads around the bowl. The coat of arms on the stand are those of Joseph Neeld Jr., a great-nephew of Philip Rundell, a founding partner of Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, a leading silversmith and jewelry firm in London. Rundell produced numerous silver variations of the Warwick Vase.

Askos claret jug with crest of the Goelet family

Askos claret jug with crest of the Goelet family

Samuel Kirk

Baltimore, Maryland; 1830–46

Silver

Museum purchase with funds provided by Louise Conway Belden in memory of Gail Chester Belden 2002.35

This American silver vessel in a shape evocative of ancient Greek goat-skin wine containers was inspired by fashionable examples from overseas. In 1801 Thomas Jefferson commissioned a Philadelphia silversmith to make an askos based on an antique bronze one excavated in Nimes, France. English white and colored glass askoi with silver mounts were produced from the 1830s onward, and elegant porcelain models were made during the late 1860s at the Minton factory in Staffordshire. English silver askoi were made as late as the 1870s. The Baltimore example shown here was probably owned by Robert Goelet or his brother Peter. The Goelet family arrived in New York from France via Holland in the late 1600s and became successful merchants and real estate developers.

Garden vase or urn

France; 1800–1825

Bronze plate, lead

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1970.636.2

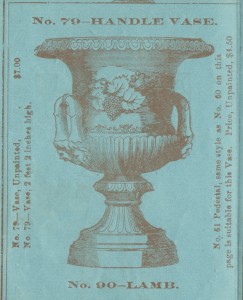

“HANDLE-VASE” from Harvey & Adamson advertisement (detail)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; soon after 1876

Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library Col. 214 86×22.2

The bronze urn in the shape of an ancient Greek or  Roman calyx krater is from a pair once displayed by Henry Francis du Pont in the Winterthur Cottage. Alsobased on ancient vessel forms is the “HANDLE-VASE” reproduced here in an advertisement by Philadelphia terracotta merchants Harvey & Adamson. The firm states proudly that some of the vases illustrated in the ad were “part of those which took a Medal at the ‘CENTENNIAL Exhibition’” in Philadelphia in 1876.

Roman calyx krater is from a pair once displayed by Henry Francis du Pont in the Winterthur Cottage. Alsobased on ancient vessel forms is the “HANDLE-VASE” reproduced here in an advertisement by Philadelphia terracotta merchants Harvey & Adamson. The firm states proudly that some of the vases illustrated in the ad were “part of those which took a Medal at the ‘CENTENNIAL Exhibition’” in Philadelphia in 1876.

Coupes, Vases, Candélabres, Sarcophages, Trépieds, Lampes & Ornements Divers

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Paris, France: A. Vincent, 1905

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NK1225 P66p F

Delaware Steeplechase and Race Association Trophy

Paul Storr

London, England; 1832–33 (vase), 1940–52 (base and engraving)

London, England; 1832–33 (vase), 1940–52 (base and engraving)

Silver, wood, brass, felt

Vase inscribed “THE DELAWARE OAKS THREE YEAR OLD FILLIES,” “ONE MILE AND A FURLONG 119 lbs.,” “PRESENTED BY MRS. MARION du PONT SCOTT,” and “THE DELAWARE STEEPLECHASE AND RACE ASSOCIATION”

Gift of Delaware Park, Inc. 1983.115a-c

Engravings illustrating ancient kraters, like those by Piranesi, inspired the design of wine coolers and sporting trophies from the 1800s onward. Paul Storr’s silver vase—showing a fox, hound, and pelt rather than classical figures—was mounted to a wooden base in the 1940s for Marion du Pont Scott. Inscribed plaques were subsequently added. The trophy base bears the names of winning horses, stables, times, trainers, jockeys, sires, and dams of fillies from 1940 to 1952 (excluding 1943). Marion Scott, a cousin of Henry Francis du Pont, married movie actor Randolph Scott and owned Virginia’s Montpelier estate, now part of the National Trust.

Related Themes: