The finest wines, when matured, are generally sent in bottles, carefully packed. Every bottle of champagne is carefully wrapped in cartridge paper, and the case lined with the same substance. This wine should never be drawn from the case until it is wanted for use. Burgundy should be kept in the same manner. The cases being filled with salt, which cannot escape, will preserve the wine fresh even in India. The bottles, however, should be more than commonly thick when designed for a voyage so long.

The finest wines, when matured, are generally sent in bottles, carefully packed. Every bottle of champagne is carefully wrapped in cartridge paper, and the case lined with the same substance. This wine should never be drawn from the case until it is wanted for use. Burgundy should be kept in the same manner. The cases being filled with salt, which cannot escape, will preserve the wine fresh even in India. The bottles, however, should be more than commonly thick when designed for a voyage so long.

Cyrus Redding, Every Man his Own Butler (London, 1839)

A young David Copperfield is banished to work at his stepfather’s dockside import-export wine and spirit warehouse:

I know that a great many empty bottles were one of the consequences of this traffic, and that certain men and boys were employed to examine them against the light, and reject those that were flawed, and to rinse and wash them. When the empty bottles ran short, there were labels to be pasted on full ones, or corks to be fitted to them, or seals to be put upon the corks, or finished bottles to be packed in casks. All this work was my work, and of the boys employed upon it I was one.

Charles Dickens, David Copperfield (1849)

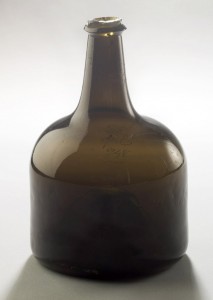

Wine bottles

Wine bottles

England; 1685–1700 (top), 1695–1710 (bottom)

Glass (nonlead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1960.1235; Museum purchase 1958.88.1

Most early 1600s English wine bottles were thin-walled and better suited for carrying wine from cask to table than for heavier-duty storage and shipping. In the 1630s, thicker walled “shaft and globe” and then (around 1670) “onion bottles” began to be produced.  Such vessels could be filled, sealed, and sometimes packed in interlocking layers in wooden boxes for shipping.

Such vessels could be filled, sealed, and sometimes packed in interlocking layers in wooden boxes for shipping.

By the late 1600s, it was recognized that the rounded shape of wine bottles hampered their placement during storage. John Worlidge, in his popular Vinetum Britannicum (London, 1678) states that laying bottles on their sides is to be commended as it keeps corks moist and damaging air out. He warns those who “place their Bottles on a Frame with their no[s]es downwards” that they risk sediment in the bottle being served in the first glass.

Wine bottle

Wine bottle

England; dated 1726

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “Iohn / DePeyster/ 1726”

Museum purchase 1960.95

Among bottles with “seals” at Winterthur, the DePeyster example is of particular interest. John (or Johannes) DePeyster of Albany, New York, served as mayor, city recorder, and Commissioner of Indian Affairs at various times. The 1726 date on this special-order vessel may record when the order for a group of bottles was placed or perhaps represents the vintage of the wine to be placed in it.

Wine bottles

Wine bottles

England; dated 1719 (bladder onion bottle), dated 1739 (octagonal bottle)

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “Cs Croon / Woodbroug / 1719” (bladder onion bottle), “*/ -R-S- / 1739” (octagonal bottle)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1961.1332, 1959.1721

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1961.1332, 1959.1721

Although the name and initials on these bottles have yet to be identified, the vessels were special orders both in terms of their shapes and the inclusion of inscribed seals. The freeblown “Croon” bottle is a “bladder onion” form made on a modest scale from around 1715 to 1740. The rare octagonal “RS” bottle is a molded form dating from around 1720 through the 1770s.

Personalized wine bottle (left)

Personalized wine bottle (left)

England; 1690–1730

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “SH”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.1723

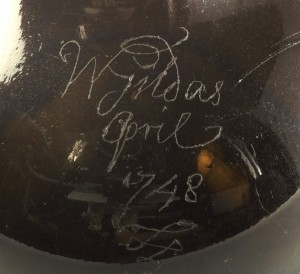

Personalized wine bottle (right)

Personalized wine bottle (right)

England; 1740–48

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “W Gildas / April/ 1748”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.1730

The above two vessels were personalized with amateurish engraving, probably by the owners. On the “SH” bottle, the initials are stipple  engraved, which called for repeated striking of the glass with a sharp tool. The shoulder of the cylindrical “W Gildas” wine bottle was inscribed with rough scratching.

engraved, which called for repeated striking of the glass with a sharp tool. The shoulder of the cylindrical “W Gildas” wine bottle was inscribed with rough scratching.

DAMON & SYLVIA, LISIMOND and CHLORIS

John Faber, Jr. (engraver) after a painting by Phillippe Mercier

Thomas and John Bowles and Son (publisher)

London, England; 1753–64

Ink on laid paper

Gift of Mrs. Waldron Phoenix Belknap 1960.754

By the time this print was published in the mid-18th century, the illustrated costumes and wine bottle forms were long out of date. The sentiment of friendship and romance shared to the accompaniment of wine, however, was timeless.

Wine bottle

England; dated 1765

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “Sidney/ Breese / 1765”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1965.2337

Beginning around 1730, bottles became more cylindrical, making it easier to place them horizontally during storage to keep corks wet and better preserve the wine. Rather than being freeblown, these bottles typically were dip-molded to create the more straight-side profile. The pushed-up undersides, known as “kicks,” left a fairly even bottom edge to the bottle and kept the rough “pontil marks” created during manufacture from scratching wooden table tops. The extra surface area created by a kick may also have helped in cooling the drink when the vessel was placed in cold water or on ice.

Applied seals on bottles sometimes carried the names or initials of owners. The larger bottle here was made for Sidney Breese, a Welshman who settled in New York City in 1730. He was a merchant specializing in imported goods, including textiles and looking glasses (mirrors). This is one of four bottles bearing the same seal.

Wine bottle (left)

England; dated 1774

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “Rolle / 1774”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.1978

Wine bottle (right)

Wine bottle (right)

Henry Ricketts & Co.

Bristol, England; 1821–35

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “W.M.C.” (seal), “PATENT” (shoulder), and “H RICKETTS & Co. / GLASS WORKS BRISTOL.” (underside)

Gift of Mrs. Harry W. Lunger 1973.452.1

In 1821 English glassmaker Henry Ricketts patented a new method of molding glass bottles. His full-size, three-part molds completed the upper portion of the bottle as well as the walls and bottom, making vessels more consistent in shape and volume. By this time, complaints and legislation to try to curb trickery by wine-sellers who sold smaller capacity bottles than were promised had a long history. Another mold was pushed up from the bottom to create the “kick” and provide the maker’s name in relief. Within about 20 years, American manufacturers patented similar methods of bottle making. The bottle shown here bears an applied and stamped seal with the original owner’s initials.

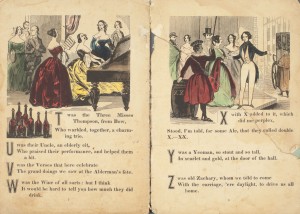

Grandmamma Easy’s Alderman’s Feast: A New Alphabet

Grandmamma Easy’s Alderman’s Feast: A New Alphabet

Albany, New York: Steele & Durrie, 1834?

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library PZ6 G75

This children’s book tells of an elegant entertainment at an alderman’s house in Bow, England. The details of the story are related in an alphabetical rhyme and include references to several alcoholic beverages. Alcohol consumption is virtually never referred to in modern children’s books but was considered a part of everyday life in the past. The following verse appears on a page adorned with wine bottles, and a musical scene:

W was the wine of all sorts: but I think

It would be hard to tell you how much they did drink.

Corkscrew and pick

Corkscrew and pick

England or America; 1725–1800

Steel

Museum purchase 1958.25.3a,b

Corkscrew and case

England; 1790–1830

Steel

Impressed “SPYERS”

Impressed “SPYERS”

Museum purchase 1961.188a,b

Corkscrew and case

Corkscrew and case

England; 1790–1850

Steel

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.1027a,b

Corkscrew (folding)

Corkscrew (folding)

United States; 1800–1850

Steel

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1961.970

Set of tools (folding) including a corkscrew

Set of tools (folding) including a corkscrew

England or United States; 1800–1900

Steel

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1965.2230

Hallmarked silver corkscrews were popular by the mid-1700s, and variations were soon available in steel and other metals. They are listed fairly often in 18th-century Pennsylvania and Virginia Gazette advertisements. The “silver and steel corkscrews” in Catharine Rathell’s 1772 Williamsburg, Virginia, ad indicate she sold such items in different materials and, presumably, at different prices.

The “peg and worm” corkscrew shown here features a pick that can be used to remove smaller corks. Two of the other corkscrews feature protective cylindrical cases that, when inserted in the loops, form handles. The simpler of the two folding corkscrews is known as an Irish bow or Irish harp. The other looks much like a modern Swiss Army knife.

Related Themes: