All delicate wines should be taken out of thin glasses. . . . The greatest objection . . . is the ease with which such glasses are broken by the servants, which renders them expensive . . . To a man of taste . . . Romanée and Lafitte would loose half their flavour in heavy coarse glass, though to the thick oily wines de liqueur or to sweet wines, [this] does not seem to apply. The glass and specific gravity of the wine should harmonize. . . . If we could divide a soap bubble in half while floating on the zephyr, we should have a perfect bowl out of which to quaff Romanée, Lafitte, or Sillery.

Cyrus Redding, Every Man His Own Butler (London, 1839)

This section highlights just a fraction of Winterthur’s collection of nearly 400 wineglasses and hints at the range of stemware available to consumers from the 1600s through the 1800s. Specific bowl, stem, and foot preferences as well as types of ornament evolved over time, all according to the latest fashion. Fashion even dictated how wineglasses were to be held. Early paintings and prints portray wine drinkers with filled glasses grasped by the foot, rather than the stem or bowl, to keep the beverage cool.

This section highlights just a fraction of Winterthur’s collection of nearly 400 wineglasses and hints at the range of stemware available to consumers from the 1600s through the 1800s. Specific bowl, stem, and foot preferences as well as types of ornament evolved over time, all according to the latest fashion. Fashion even dictated how wineglasses were to be held. Early paintings and prints portray wine drinkers with filled glasses grasped by the foot, rather than the stem or bowl, to keep the beverage cool.

Attempts to strictly assign particular glass forms to specific beverages can meet with frustration, as preferences and availability changed. Until a wider variety of affordable stemware became available during the mid- to late 1700s, few but the wealthiest consumers could acquire specific vessels for specific uses.

On average, wineglasses from the early 1700s are of smaller capacity than their later counterparts, perhaps reflecting the cost of wine as well as the alcohol content. Some period terms seem to indicate glass sizes. The word cordial, referring to strong wines typically fortified with brandy, was associated with stemmed, small-bowl vessels. So-called “toastmasters glasses,” at a time when it was not uncommon to drink 14 to 20 toasts at a single event, are also of smaller capacity. In contrast, the words goblet and rummer usually referred to large-capacity vessels. Champagne has been consumed from generic wineglasses, tall flutes, and more modern wide-bowl types like those popular today.

Passglas

Passglas

Germany or The Netherlands; 1600‒1625

Glass (nonlead)

Gift of Richard and Pam Mones 2011.54

Tall glasses like this one probably more often were used for serving ale or beer than wine. As the name passglas implies, such vessels were intended to be shared and sometimes were passed among several drinkers. The horizontal rings are said to indicate the amount to be drunk by each person. At the time this vessel was made, northern European glassware was also arriving at colonial American settlements.

Wineglass

Wineglass

London, England, or continental Europe (Belgium?); about 1680

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “SPEQVE METU QVE PAVET” and “MATORA CEDUNT”

Gift of Richard and Pamela Mones 2011.34

This wineglass is an elegant example of late 17th-century innovations in manufacturing techniques, specifically the introduction of larger quantities of lead. Research into new glass recipes reached its first great success inLondonat the hands of George Ravenscroft. This vessel was possibly made inLondonand decorated in continental Europe; the wheel-engraved ornament is a type usually associated with Nuremburg, now a part ofGermany. The overall shape of the glass imitates fashionable Venetian (non-lead) types.

The meaning of the Latin inscriptions on either side remains obscure, but they may be mottos associated with a particular family. Glasses of this type, typically without engraved ornament, have been excavated in America.

“Wrythen” ale glass

England; 1690–1720

Glass (lead)

Museum purchase 1978.196

Salver

Salver

Jacobus Van der Spiegel

New York, New York; about 1700

Silver

Inscribed “Myndert Schuyler / b. 1672 d. 1755” and “M+S”

Gift of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.2597

As documented in early paintings and prints, at some elegant events, wineglasses were served on small metal trays, or salvers. Thomas Blount’s Glossagraphia (1661) states that a “Salver . . . is a new fashioned peece of [silver], broad and flat, with a foot underneath, and is used in giving Beer, or other liquid thing[s], to save the Carpit or Cloathes from drops.” Merchant Myndert Schuyler, whose name appears on this salver, served twice as mayor of Albany,New York, and was also Commissioner of Indian Affairs and a deacon in the Dutch Reformed Church.

Wineglass

Wineglass

England; 1725–40

Glass (lead)

Museum purchase 1968.116

Based on archaeological evidence and advertisements for glassware “newly arrived” fromLondon, Liverpool, and Bristol, English glassware remained popular inAmericathroughout the 1700s. This was due in part to trade restrictions but also because Englandwas a leader in glass design. The glasses here show just a few of the many popular stemware types that made their way to this continent.

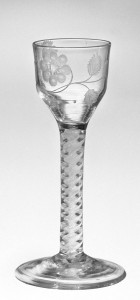

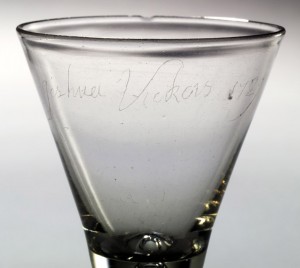

Wineglass

England; dated 1729

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “Joshua Vickers 1729”

Gift of Dr. Thomas M. McMillan III 2006.3.34

Although most English glasses had no inscriptions, this trumpet-shape, or drawn-stem, glass is personalized “Joshua Vickers 1729” in diamond-point.

Goblet and wineglasses

England; 1745–70 (air twist stem), 1755–80 (white twist stem), 1770–1810 (faceted stem)Glass (lead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1968.712; Museum purchase 1968.311.2; Gift of Barbara A. James 2007.23.4

Molded ribbing, wheel-engraved ornament, and air-or opaque-twist stems as well as cut facets ornament some stemware excavated in America.

Goblet with cover, or pokal

Goblet with cover, or pokal

John Frederick Amelung’s New Bremen Glassmanufactory

Frederick, Maryland; 1791–93

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “G. J. Schley”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.47a,b

The large, covered “pokal” shown here reflects continental European tastes and would have appealed to German Americans. Made for riflemaker and tavernkeeper George Jacob Schley, a founder of Frederick, Maryland, this vessel portrays a fish, which may be a pun on the owner’s name. Schleie in German refers to a fish in the carp family. The German word pokal derives from boccale, Italian for mug or jug. A goblet resembling this one is signed by famous early glassmaker John Frederick Amelung.

Drinking glass with Pennsylvania coat of arms

Drinking glass with Pennsylvania coat of arms

Pennsylvania; 1865–85

Glass (lead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.3061

Wineglass

Wineglass

Probably New Jersey; 1810–35

Glass (nonlead)

Museum purchase 1957.90.5

The glass with the Pennsylvania coat of arms is probably from one of the 28 glasshouses and 15 glass-cutting establishments active in the state from 1843 onward. The aqua tint of the second wineglass is the result of iron impurities and was a common feature of wares made by factories whose primary products were window and bottle glass.

Wineglass

Wineglass

Bohemia (Czech Republic) or Germany; 1760–80

Glass (nonlead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1958.1420

Goblet

Goblet

Bohemia (now Czech Republic); 1840–60

Glass (nonlead)

Gift of Greta Layton Schutt 1994.41

From the early 1600s onward, Americans imported drinking vessels from continental Europe, England, and eventually Ireland. Although some goods specifically targeted American markets, others would have been attractive to European consumers as well. The brightly painted white wineglass is slightly irregular in shape and bears somewhat unsophisticated motifs. Such objects would have appealed to a middle-income market. The red-stained goblet with a stag motif would have been more expensive, as it has more elegantly executed cut and engraved ornament.

Wineglass

New England Glass Company

East Cambridge, Massachusetts; 1855–70

Lead glass

Gift in memory of Cecile Ferland 2002.21.5

This small “ruby overlay” glass displays a grapevine engraved through a layer of red glass to expose the colorless core. It was made in America but engraved in a continental European style by German immigrant craftsman Louis Frederick Vaupel.

Oversize goblets

Oversize goblets

England; 1690–1715

Glass (lead)

Gift of Pam and Richard Mones 2005.42; Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1963.685

From at least as early as the Middle Ages, oversize drinking vessels were popular for communal use. In a time “before germs,” they were passed around and shared among guests.

Oversize goblet

Oversize goblet

England; 1715–40, with engraving probably from 1736 and 1849

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “Anne Woodbridge / Augst – 17th 1736” and “Ann Willing Morris / November / 1849”

Gift of Jeanie Morse Littell Winslow and Julian Dala Winslow 2004.29

This trumpet-shape “drawn stem” glass bears unusual diamond-point inscriptions, perhaps engraved with the ladies’ rings. Similarly executed names and dates commemorating weddings and other events are found on early window panes in Virginia. Anne Woodbridge is yet to be identified. The name Ann Willing Morris is thought to refer to a descendant of Charles and Anne Shippen Willing, whose portrait by Robert Feke is in the Winterthur collection.

Wine cup

Wine cup

Jingdezhen, China; 1600–1610

Porcelain (hard paste)

Museum purchase with funds provided by Mrs. Alfred P. Harrison 1978.28

Although glass is much more common, wine vessels in other materials also have a long history. This tiny porcelain wine cup matches types excavated at Jamestown, Virginia. Although it resembles a tea bowl, tea was virtually unavailable to Westerners in the 1600s. This cup was part of the cargo of the Dutch East Indiaman, the Witte Leeuw (White Lion) which sunk at St. Helena Island, off the coast of Africa in 1613.

Goblets or wine cups

Goblets or wine cups

Jingdezhen, China; 1690–1710 (blue and white), 1840–60 (polychrome and gilt)

Porcelain (hard paste)

Gift of Leo A. and Doris C. Hodroff 2000.61.67; Gift of Mrs. C. Henry Reeves, Jr. 1981.35

Although glass is much more common, goblet-shape wine vessels in other materials also have a long history. The porcelain ones shown here span two centuries. The beautifully painted blue and white cup would have been quite costly. Similar porcelain goblets were recovered from a Chinese ship that sank near Vietnam about 1695. Those drinking vessels were likely on their way to European consumers. The gilt and enameled cup bears ornament specifically intended for the Western market.

Although glass is much more common, goblet-shape wine vessels in other materials also have a long history. The porcelain ones shown here span two centuries. The beautifully painted blue and white cup would have been quite costly. Similar porcelain goblets were recovered from a Chinese ship that sank near Vietnam about 1695. Those drinking vessels were likely on their way to European consumers. The gilt and enameled cup bears ornament specifically intended for the Western market.

Goblet or wine cup

Staffordshire or Yorkshire, England; 1810–20

Earthenware (silver luster pearlware)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1958.1272

This white pearlware cup would have appealed to a middling-income market. It imitates more-costly metalwork in shape and in its “silver luster” border, created using platinum.

Standing cup or chalice

Johann Christoph Heyne

Lancaster, Pennsylvania; 1760–80

Pewter

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1962.604

Pewter goblets were more costly than most glass examples but were less expensive than silver and gold ones. The large size of the pewter cup shown here may indicate it was created for church use.

Goblet

John Curry

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1820–40

Silver

Museum purchase 1988.7

The applied, stamped decoration on this silver goblet combines musical instruments and a grapevine in celebration of the traditional pairing of music and wine. The costliness of such an object suggests it was destined for a wealthy home. Period documents for Curry and his sometime partner William Preston list knives, forks, and other cutlery more often than hollowware forms, suggesting that the goblet was not typical of the items they created.

Flute

Europe; 1700–1800

Cow horn

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1960.1108

Goblet or wine cup

United States; 1790–1840

Probably white rhinoceros horn

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1961.510

Goblets made in organic materials typically would have been less expensive than metal, glass or ceramic drinking vessels. Cow horn was readily available and, like rhinoceros horn, required pressure, heat, and steam when shaping. The examples shown here were finished on a lathe.

Related Themes: