As has been true since ancient times, travelers sometimes like to carry a small amount of alcohol with them in flasks. Those shown here are among the nearly 300 glass flasks in the Winterthur collection and probably held strong drinks such as whiskey or gin; earlier examples commonly carried wine. Modest-size flasks were made in various styles, price ranges, and materials in the 1700s and 1800s—metal, glass, ceramics, wood, and horn—and might be sealed with stoppers or lids. The term pocket bottle refers to the fact that men’s jackets or coats traditionally included large pockets where such vessels could be carried. Flasks sometimes carry names, dates, and inscriptions.

As has been true since ancient times, travelers sometimes like to carry a small amount of alcohol with them in flasks. Those shown here are among the nearly 300 glass flasks in the Winterthur collection and probably held strong drinks such as whiskey or gin; earlier examples commonly carried wine. Modest-size flasks were made in various styles, price ranges, and materials in the 1700s and 1800s—metal, glass, ceramics, wood, and horn—and might be sealed with stoppers or lids. The term pocket bottle refers to the fact that men’s jackets or coats traditionally included large pockets where such vessels could be carried. Flasks sometimes carry names, dates, and inscriptions.

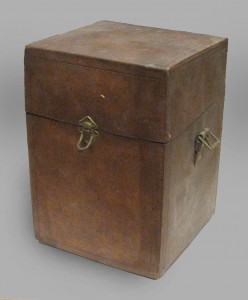

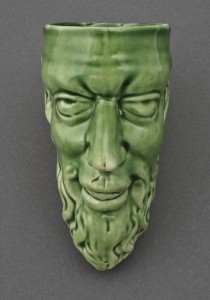

Other vessels for drinking “on the go” were stirrup cups, presumably named because they were used by mounted riders before a hunt. Lacking a flat base, the cups needed to be drunk dry before they could be set down. Common shapes include animals or human heads.

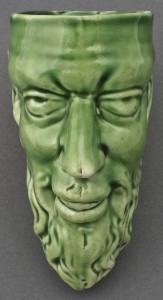

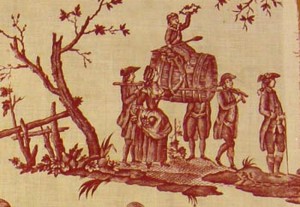

Textile panel (details)

Textile panel (details)

Petitpierre et Cie

Nantes, France; 1790–1802

Cotton

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.3271

This printed pattern, known as “La maison brulante” (The house is burning), is one of at least two different versions. The scenes were inspired by Floquet’s 1780  opera Seigneur Bienfaisant and portray a burning house where a man is said to have rescued a child. A huge winepress is nearby, being worked by a man walking within a large wheel. Nearby are casks and other workers, including a harvester arriving with more grapes. We also see a festive procession with a boy carried astride a large wine barrel.

opera Seigneur Bienfaisant and portray a burning house where a man is said to have rescued a child. A huge winepress is nearby, being worked by a man walking within a large wheel. Nearby are casks and other workers, including a harvester arriving with more grapes. We also see a festive procession with a boy carried astride a large wine barrel.

As I remember, it was almost midnight when we took our leave. We had had some biscuit and dried fish for supper, and Steerforth had produced from his pocket a full flask of Hollands [gin], which we men . . . had emptied. We parted merrily; and as they all stood crowded round the door to light us as far as they could upon our road.

Charles Dickens, David Copperfield (1849)

Flask or pocket bottle

Flask or pocket bottle

Johann Christoph Heyne

Lancaster, Pennsylvania; 1756–80

Pewter

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1955.623

Records dating to 1775 from the office of “the commissioner of purchases in Lancaster” indicate Johann Christoph Heyne had recently been paid for making canteens and other items “for riflemen.” Canteens could hold water or alcohol. A second flask, in another collection, may be from the same mold as Winterthur’s example and is inscribed “Col. Christ. Lauer / 1776.”

Flask or pocket bottle

Flask or pocket bottle

Probably Henry William Stiegel Glassworks

Manheim, Pennsylvania; 1769–74

Glass (nonlead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.3144

This amethyst “diamond-daisy” pattern flask is one of several at Winterthur made from the same mold. Such flasks were also made in cobalt-blue or colorless glass and are associated with Henry William Steigel, who primarily made bottles, window glass, and German-style beverage and tableware. The Townshend Acts of 1767, which taxed imported manufactured goods, are thought to have spurred an increase in Steigel’s glass production.

“SUCCESS TO THE RAILROAD” figured flask or pocket bottle

Probably Keene Glass Works

Probably Keene Glass Works

Keene,New Hampshire; 1830–45

Glass (nonlead)

Gift of Mr. Charles van Ravenswaay 1968.207

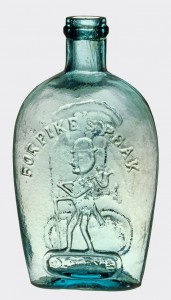

“FOR PIKE’S PEAK” figured flask or pocket bottle

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 1859–70

Glass (nonlead)

Glass (nonlead)

Further inscribed “OLD RYE” and “PITTSBURGH PA”

Gift of Mr. Charles van Ravenswaay 1968.199

Nineteenth-century American glass “figured flasks” feature a variety of images, from purely ornamental motifs to portraits of political and military heroes, patriotic themes, and references to technological innovations such as the railroad. Reflecting the same spirit of enthusiasm over new opportunities, the “FOR PIKE’S PEAK” flask refers to the 1859 gold rush. Below the figure is the phrase “OLD RYE” referencing whiskey, and on the reverse an American eagle is above a “PITTSBURGH PA” inscription, naming the place of manufacture.

Bear, squirrel, and fish flasks or pocket bottles

Rudolph Christ pottery

Winston-Salem, North Carolina; 1810–30

Earthenware

Museum purchase 2010.26; Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1967.1632, 1959.2147

Rudolph Christ’s pottery was active in a North Carolina Moravian community—home to  German emigrants escaping religious persecution—and produced both German-style pottery and imitations of fashionable English wares. Rare flasks from the pottery include graduated sizes of fish, squirrel, and other forms. Most were available in more than one color, with green-glaze, blotchy “tortoiseshell,” and dark brown being most popular.

German emigrants escaping religious persecution—and produced both German-style pottery and imitations of fashionable English wares. Rare flasks from the pottery include graduated sizes of fish, squirrel, and other forms. Most were available in more than one color, with green-glaze, blotchy “tortoiseshell,” and dark brown being most popular.

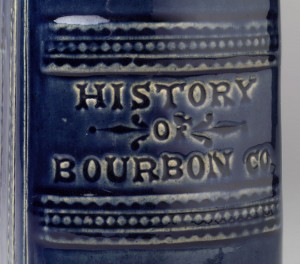

Whiskey flask

Whiskey flask

United States; 1825–75

Stoneware

Inscribed “HISTORY/ OF / BOURBON CO.”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1967.1876

Although it probably didn’t fool anyone, this book-shape whiskey flask reflects a long history of alcohol-filled glass bottles supposedly being hidden within hollowed-out books. The opening on the top could be sealed with a cork.

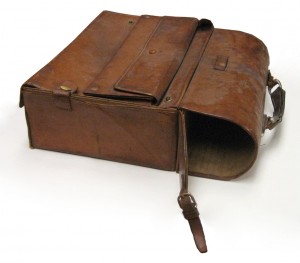

Liquor box and picnic case

Liquor box and picnic case

Probably London, England; 1900–1930

Leather, metal, press board (?), cloth (picnic case)

Inscribed “H. DU P.”

Museum Archives OB 499, OB 562

For those who preferred to pour their beverages from a wine bottle when away from home, special portable containers were available. The square liquor box is a descendent of portable wooden cellarets and is slotted to  receive four wine bottles. The leather picnic case has a wine bottle includes a mailbox-like slot for a bottle as well as spaces for food, plates, and flatware. Both cases bear the initials of Henry Francis du Pont.

receive four wine bottles. The leather picnic case has a wine bottle includes a mailbox-like slot for a bottle as well as spaces for food, plates, and flatware. Both cases bear the initials of Henry Francis du Pont.

Boot-shape glass

Boot-shape glass

England; 1750–1800

Glass (lead)

Gift of Dr. Thomas M. McMillan III 2006.3.13

The traditional name for some types of drinking vessels suggests an association with horsemen taking a quick drink in the saddle, without dismounting. Boot glasses, some of them quite large, are known in Germany and Italy as early as the late 1500s. They were intended to be held until the entire contents had been drunk.

Satyr (?) head stirrup cup

Satyr (?) head stirrup cup

Staffordshire, England; 1760–90

Earthenware (creamware)

Museum purchase 1959.67

Stirrup or coaching glass

England; 1800–1830

Glass (lead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1967.859.2

The green cup shown here probably represents a satyr, a mythical creature associated with Bacchus and excessive drinking. Ancient ceramic stirrup cups were often in animal-head forms and are known as rhytons. Ceramic and silver stirrup cups from the late 1700s and 1800s sometimes portray animals associated with the hunt, such as hounds, foxes, or hares. Footless glass stirrup cups survive in smaller numbers than their ceramic counterparts.

Antiquités Etrusques, Grecques, et Romaines Tirées du Cabinet du M. William Hamilton, vol. 1, pl. 49; vol. 2, pl. 63

Pierre-François Hugues D’Hancarville

Naples, Italy: W. Hamilton, 1766/67

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library NK4624 H22co PF

These reproductions of engravings of animal-head drinking cups come from the catalogue of William Hamilton’s collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. Hamilton and other members of London’s Society of Dilettanti were influential in inspiring reproductions of ancient objects and buildings.

These reproductions of engravings of animal-head drinking cups come from the catalogue of William Hamilton’s collection of Greek and Roman antiquities. Hamilton and other members of London’s Society of Dilettanti were influential in inspiring reproductions of ancient objects and buildings.

Related Themes: