From the 1650s onward, colonists acquired an ever-broadening variety of wines. Most fine wines continued to be imported, but large landowners also began to plant domestic vineyards, and alcoholic beverages could even be made at home from recipes in cookbooks. One 1867 Philadelphia publication entitled Six Hundred Receipts, Worth Their Weight in Gold included recipes for 18 types of wine, 26 brandies, 14 “cottage beers,” 7 rums and whiskies, and 6 gins along with others for cider and cordials.

From the 1650s onward, colonists acquired an ever-broadening variety of wines. Most fine wines continued to be imported, but large landowners also began to plant domestic vineyards, and alcoholic beverages could even be made at home from recipes in cookbooks. One 1867 Philadelphia publication entitled Six Hundred Receipts, Worth Their Weight in Gold included recipes for 18 types of wine, 26 brandies, 14 “cottage beers,” 7 rums and whiskies, and 6 gins along with others for cider and cordials.

Wealthy consumers could choose from a variety of drinks to suit different occasions, and those of more modest means naturally acquired less-costly beverages. In 1770, Philadelphia’s One Tun Tavern sold beer, gin, and toddy (rum and hot water) for three shillings, cider for two shillings, and punch for one shilling sixpence. Wines varied in price, and preferences varied by location. William Ellery, who visited Durham, Connecticut, in 1778, wrote in his journal that

the good people of Connecticut when they form the semicircle round the warm hearth, and the Tankard sparkles with Cyder, are as merry and sociable as New Yorkers are when they tipple the mantling [foaming?] Madeira.

Although bottles and decanters used in Britain and America typically had no inscriptions, some did have the names of wines or spirits engraved or painted in enamel on the vessel. Inscribed hanging labels and stoppers were also available.

Coming to terms with alcoholic beverages

- Ale—A type of beer brewed from malted barley.

- Beer—Brewed by steeping a starch source (malted barley/wheat) in water and fermenting with yeast. Can be flavored and preserved by adding hops. Brewed stronger in the 1600s and 1700s and served in smaller glasses. Weaker beers were called “small.”

- Cider and perry—Typically fermented from fruit other than grapes—cider from apples; perry from pears. Alcohol content is similar to ales and beers.

- Cordial—Made from brandies and other distilled spirits. Flavored with berries and herbs; served in small-capacity glasses. Used socially and medicinally.

- Mead—Fermented from honey. Can be sweet or dry. Recipes often included spices, grain, or fruit.

- Spirit—Strong beverages containing ethanol. Made by distilling fermented grain, fruit, or vegetables. Common types include whiskey (usequebaugh) distilled from grain; gin from grain or malt and flavored with juniper berries; and rum, from molasses and other sugar-cane products. Brandy is a spirit distilled from wine.

- Wine—Typically refers to an alcoholic beverage fermented from grapes, other fruit, or flowers. Classed by place of origin, color, sweetness or dryness, and still or sparkling qualities. Commonly divided into table or sweet wines, such as sherry or port, in the 1600s and 1700s.

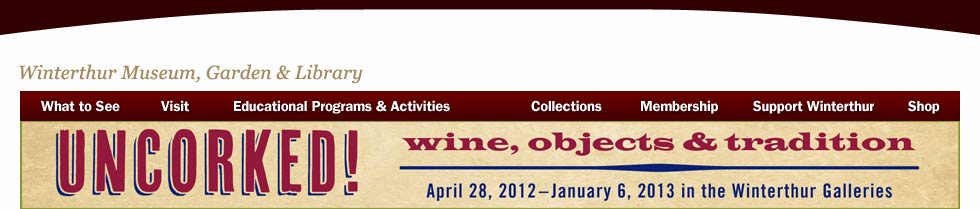

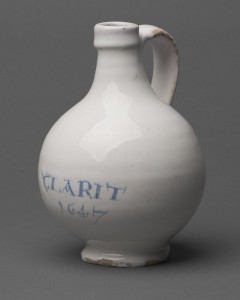

Jugs or bottles

Probably Southwark, London; dated 1647, 1648, 1658

Earthenware (delftware)

Inscribed “CLARIT/ 1647,” “SACK/1648,” “WHIT/ 1658”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1964.680, 1960.760; gift of anonymous donor 1984.75

These vessels, inspired by the shapes of popular German stoneware “bearded man jugs,” were made in England from the early 1600s onward. Inscribed and dated examples are rare. The term sack on one bottle shown here is sometimes associated with the French vin sec (dry wine) or German wein sekt (sparkling wine). Typically, sack refers to southern European wines also known as sherry-sack, Malaga Sack, Canary Sack, or Madeira Sack, from Spain or the Canary Islands. Claret first referred to pale wines but by 1600 was commonly applied to certain reds, especially from France; “WHIT” is thought to be an abbreviation of “White Wine.”

Perhaps the most obvious division of wines is according to colours, as red and white; but another arrangement . . . considers them as 1, dry and strong, as Port, Sherry, and Madeira; 2, dry and light, as Hermitage, Claret, Burgundy, or Hock; 3, brisk, effervescing, and sparkling, as Champagne; 4, sweet, as Malmsey, &c.

Thomas Webster, An Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy (New York, 1845)

Claret decanter and wineglasses

Claret decanter and wineglasses

Possibly decorated at William Beilby’s shop

Newcastle upon Tyne, England; about 1765

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “CLARET” (decanter)

Museum purchase 1975.44.2, .42a,b, .43.1-.2

“CLARET” wine label

Possibly United States; 1780–1800

Silver

Promised gift of Wendy Cooper

The inscribed panel on the decanter shown here imitates metalwork labels that sometimes hung by chains on such vessels. The elegantly painted ornament on the decanter and glasses may have been executed by William or Mary Beilby, who were active during the 1750s and 1760s as enamelers and gilders in Newcastle on Tyne, England. In a 1770 Pennsylvania Gazette, merchant Daniel Drinker of Philadephia offered for sale “best cut stem enamelled and plain wine glasses.”

The silver “CLARET” wine label has a history of ownership by John Brown, a Revolutionary War hero, successful merchant, and ship owner in Providence, Rhode Island.

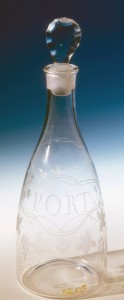

Port decanter

Port decanter

England; 1765–75

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “PORT”

Museum purchase 1969.47

Port is typically associated with the Douro valley near Porto (or Oporto) in Portugal. Like Madeira, port is fortified with a brandy-like grape spirit known as aguardente, which stops the fermentation process and allows the sugars to boost the alcohol content. The production of Portuguese wines was encouraged by the English during the 1700s, in part due to England’s hostilities with France. By the mid-1700s, port was available in America by the cask or bottle. Philadelphia merchant Joseph Wharton advertised in a 1773 Pennsylvania Gazette, “Genuine SHERRY, LISBON & MADEIRA WINE, In Pipes and Quarter Casks; BRANDY, in Hogsheads; AND EXCELLENT PORT WINE, In Hampers, of three Dozen each.”

Sherry bottle

Sherry bottle

Probably England; 1770–1800

Glass (nonlead)

Seal inscribed “SHERRY”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1960.1138

Unlike port, which is associated with Portugal, sherry takes its name from Xeres (now Jerez de la Frontera) near Cadiz, Spain, where it was first produced on some scale. The prestigious Walpole Society, of which Henry Francis du Pont was a member, presented this bottle to du Pont when he announced his intention to open Winterthur as a museum.

Port and sherry labels

Port and sherry labels

John Robins

London, England; 1804–5

Silver

Inscribed “PORT” and “SHERRY”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1970.1251.1, .2

Labels that identify the contents of bottles or  decanters are mentioned in period ads and inventories and were often made in metal. Silver labels might bear the beverage name in engraved or pierced letters; enameled base metal versions might display the drink name in painted or printed lettering. The silver port and sherry labels shown here were made as a set.

decanters are mentioned in period ads and inventories and were often made in metal. Silver labels might bear the beverage name in engraved or pierced letters; enameled base metal versions might display the drink name in painted or printed lettering. The silver port and sherry labels shown here were made as a set.

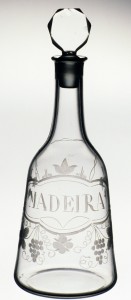

Madeira decanter

Madeira decanter

England; 1760–75

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “MADEIRA”

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Charles E. Merrill Trust for the Purchase of English Objects 1976.165

Madeira, a fortified white wine associated with an island off the northwest coast of Africa, was available in Americaby 1700. Although it could be bought in shops, some Americans imported Madeira directly from the island, as reflected in Virginia Gazette ads, including one from 1771:

THE Schooner Francis, Captain Jacob Cooper, will sail from York River, in about three Weeks, for Madeira. Any Gentlemen who want Wine from that Island are desired to send their Letters to the Care of William Stevenson, in York Town, to go by the said Vessel.

In 1764 Burlington “West Jersey” merchant Ann Hume advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette that she had newly imported from London, including “best quart and pint decanters, labelled Madeira.” In a 1770 ad, prominent Philadelphia merchant Joseph Stansbury offered “a few Prussian Decanters labelled Madeira.”

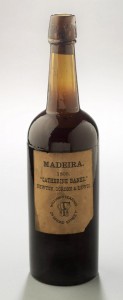

Wine bottle with Madeira

Wine bottle with Madeira

Probably England; about 1805

Glass (nonlead)

Paper label inscribed “MADEIRA. / 1805. / ‘CATHERINE BANKS.’ /NEWTON, GORDON & LEWIS.” and “WHF” monogram

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.1883

Wine bottle with Madeira

Wine bottle with Madeira

Probably England; 1790–98

Glass (nonlead)

Inscribed “R. LENOX” (seal) and “LENOX MADEIRA. / [diamond with ‘9’] / Imported by the late Robert Lenox, / Esq. via Philadelphia, in 1796. / Bottled . . . summer of 1798. / re-bottled . . . June 1888” (paper label)

Museum purchase 1985.55

According to period records, the ship Catharine Banks, whose name appears on a bottle shown here, transported Madeira to America during the early 1800s. The wine was probably bottled in England before export. The initials “WHF” may refer to William H. Fearing, a member of a New York family of merchants and importers, for whom the wine was rebottled later in the century. The second bottle also contains Madeira and features a seal bearing the name of the importer as well as a detailed label describing the history of the contents.

Wine label

Wine label

Possibly United States; 1780–1800

Silver

Inscribed “TENERIFFE”

Promised gift of Wendy Cooper

“Tenerife” or “Teneriffe” is a type of white wine sometimes known as Canary, Palm, or Vidonia and is associated with the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa. Like the “CLARET” label shown above, the “TENERIFFE” label has a history of ownership by John Brown who served with honor during the Revolutionary War hero and was a successful merchant and ship owner in Providence, Rhode Island.

Gin, wine, and rum decanters

Gin, wine, and rum decanters

United States; 1820–45

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “GIN,” “WINE,” “RUM”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.3306a,b, .3304a,b, .3303a,b

As was true of more-costly enameled or engraved decanters, some that were relief-decorated and mold-blown bore beverage names and were available in sets. By 1829 inscribed molded decanters were in production at the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company in Massachusetts, the Brooklyn Flint Glass Works, and others. A brandy decanter from this set is shown below.

Brandy decanter

Brandy decanter

United States; 1820–45

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “Brandy”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.3305a,b

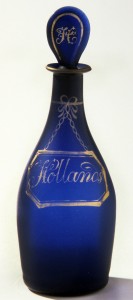

Hollands (gin) decanter

Hollands (gin) decanter

Probably Bristol, England; 1800–1810

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “Hollands” and “Brandy”

Gift of Mrs. Harry W. Lunger 1973.459.1a,b

The term brandy is from the Dutch word brandewijn, meaning burnt (i.e., distilled) wine. As with gin and grain-based beer and whiskey, a “still” featured in the brandymaking process. Although grape-based brandy was popular, some was made from other fruit. In 1774 Philip Vickers Fithian, a tutor inVirginia, wrote in his journal, “In the Evening the Colonel began with a small Still to distill some Brandy from a Liquor made of Pisimmonds [persimmons].”

The mate to the blue decanter is inscribed “Brandy” and, like this example, has a gilt label imitating metal types with chains. Blue decanters are usually associated with spirits, though rare ones bearing wine names also survive. The title “Hollands” is a shortened form of Hollands Geneva, a term eventually corrupted to “gin.” Blue glass decanters were sold in New York from the 1770s onward, and in 1807 a South Carolina merchant offered “Liquor frames with gilt blue decanters.”

Champagne

Champagne or ice decanter

Champagne or ice decanter

England; 1780–1810

Glass (lead)

Museum purchase 1991.48a-c

Champagne flute

Champagne flute

United States, England, or Ireland; 1815–35

Glass (lead)

Gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Geoghegan in honor of John T. and Patricia R. Geoghegan 1994.113.1

Although the elite inEnglanddrank champagne from the mid-1600s onward, it did not become popular in America until the early 1800s. A visitor to Washington, D.C., in 1819 wrote,

You will be much judged . . . by your Champagne . . . the Americans prefer the sweet and sparkling. [A] dinner or supper is prized and talked of exactly in proportion to the quantity of Champagne given and the noise it makes in uncorking.

Special champagne or “ice decanters” include a glass pocket for ice, on the underside, fitted with a cover. Variations with side ice pockets can also be found. By the early 1800s, Americans were making tall “flute” wineglasses that resembled their foreign counterparts.

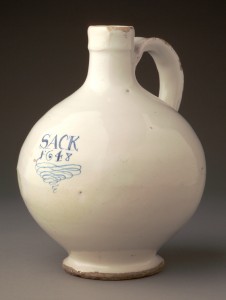

Trade card for Hammondsport Wine Company (two views)

Hammondsport, New York; about 1893

Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library Col. 46 68×155.46

A reduction in import duties during the mid-1800s led to the increased popularity of champagne and other beverages in America. This leaflet lists wines produced by Hammondsport along with their shipping prices and notes with pride that the company is represented in the “Vinticulture department” at the World’s Columbian Exposition—also known as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

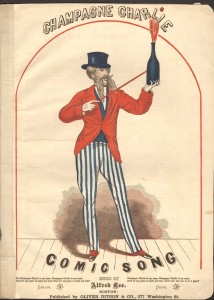

“Champagne Charlie” sheet music

“Champagne Charlie” sheet music

Alfred Lee (composer)

Oliver Ditson & Co.

Boston, Massachusetts; 1867+

Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library Col. 240 73×171

In 1867 London music hall entertainer George Leybourne wrote the lyrics for, and first performed, the song “Champagne Charlie,” which satirized the upper class for its affection for champagne. The song’s theme follows the activities of a somewhat foppish man who spent many an evening drinking champagne with varied companions about town. As evidenced by the song sheet published in Boston, the music’s popularity quickly spread to America, where it would inspire other music, plays, and even movies. (For Charlie shown in a different light, see Temperance.)

Other Fruit-Based Alcoholic Beverages

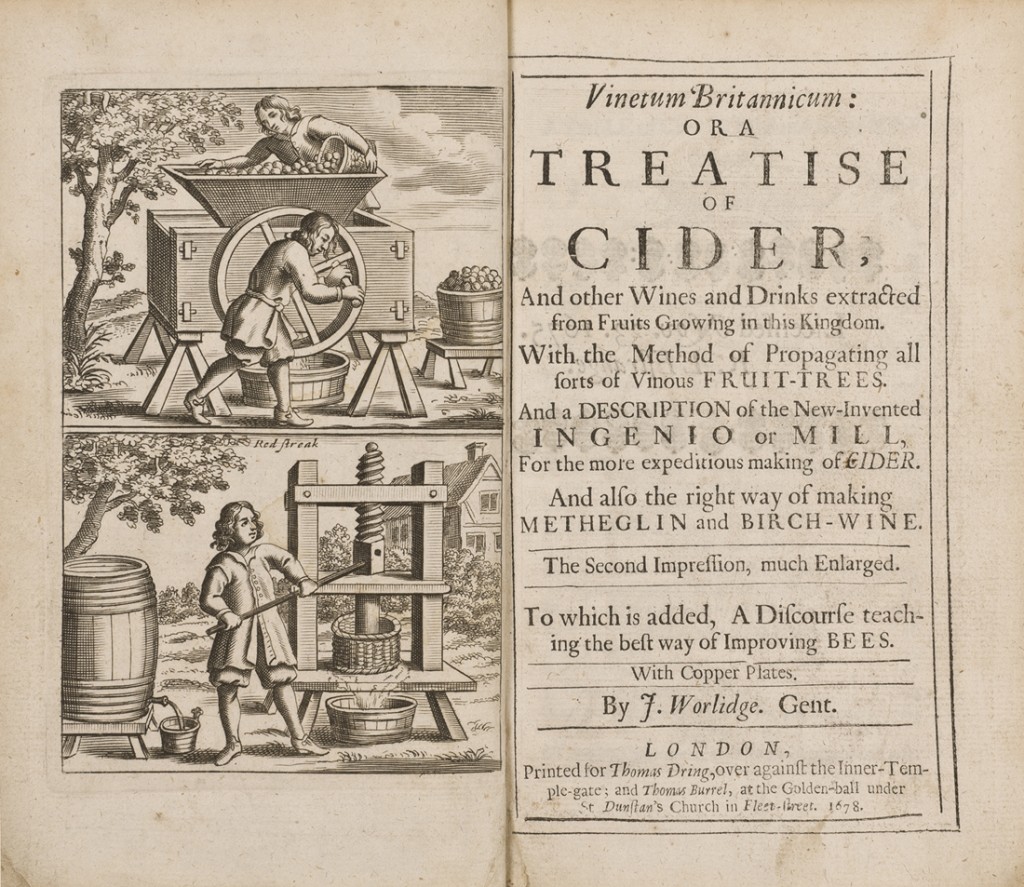

Vinetum Britannicum: or, A treatise of cider, and other wines and drinks extracted from fruits growing in this kingdom . . .

John Worlidge

London, England: Printed for Thomas Dring, 1678

Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library TP504 W92

Worlidge’s Vinetum Britanicum focuses primarily on cider, with politically-conscious sections titled “That Cider and other Juices of our English Fruits are the best Drinks for This Country [England]” and “Cider [is] prefer’d to forreign Wine.” He tells how to plant apple trees, harvest the fruit, and then ferment the cider, noting that barrels formerly used for wine are preferable. Also included are remarks on fruit wines as well as metheglin (made from honey) and the best vessels for storing alcoholic beverages.

Cider jug or pitcher

Cider jug or pitcher

Jingdezhen, China; 1780–1800

Porcelain

Inscribed “DEAR. Tom / This. Brown / Jug. Which / Now. Foams / With. Mild / Ale Out . Of.”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1958.2953

Although the Englishman on this pitcher holds a note referring to his foaming jug of ale, barrel-shape jugs are often associated with cider—a drink fermented from apples. The “DEAR TOM” inscription suggests the vessel was a special commission.

Cider jug or pitcher

Jingdezhen, China; 1805–15

Porcelain

Gift of Leo A. and Doris C. Hodroff 2000.61.78

This floral-border pitcher bears fashionable Chinese “mandarin” scenes and, like the previous jug, may have had a low-dome lid.

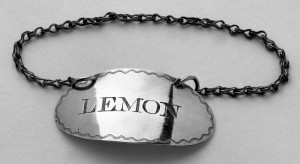

“LEMON” label

“LEMON” label

Nathaniel Vernon & Co.

Charleston, South Carolina; 1802–8

Inscribed “LEMON”

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Bissell Fund 1968.273

The term lemon, on this rare South Carolina label, may refer to “lemon cordial,” a sweet alcoholic beverage distilled from lemons, initially thought to have medicinal virtues. The mark on the label indicates it was made by Nathaniel Vernon, who is thought to have begun his career in New York before moving to Charleston in 1802. Vernon worked in gold and silver himself and sold a variety of imported metalwork.

Cherry and whiskey decanters

Cherry and whiskey decanters

Boston and Sandwich Glass Company

Sandwich, Massachusetts; 1825–45

Glass (lead)

Inscribed “CHERRY” and “WHISKEY”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.3260a,b, .3258a,b

Of the decanters shown here, the one inscribed “CHERRY” is rarer. The name could refer to a cherry-based wine, to fortified “Cherry Brandy,” or to the more punch-like “Cherry Bounce.” Such drinks were imported and made locally. A Scottish parson named Robert Rose, who worked in Virginia, recorded in June 1748 that he “Came up to Capt. Thomson’s, preached and dined, and . . . Drunk a Spirit made of cherries.” Whiskey, or usquebaugh—from the Irish uisce beatha or Scottish uisge beatha meaning “water of life”—was distilled from a fermented mash of grain.

Related Themes: