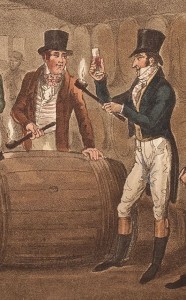

Detailed winemaking instructions were available in periodicals, wine books, and many cookbooks. These explained that wooden barrels or casks were needed for the preparation, storage, and shipping of wines and discussed the importance of choosing the correct woods for fermentation. The best methods of cleaning, reusing, and storing casks were suggested, and guidance was provided regarding wine-bottle selection, bottling methods, and cellar construction.

Detailed winemaking instructions were available in periodicals, wine books, and many cookbooks. These explained that wooden barrels or casks were needed for the preparation, storage, and shipping of wines and discussed the importance of choosing the correct woods for fermentation. The best methods of cleaning, reusing, and storing casks were suggested, and guidance was provided regarding wine-bottle selection, bottling methods, and cellar construction.

By the early 1600s it was common knowledge that light was the enemy of wine preservation. In England, thin-walled bottles used purely for serving at the table began to be replaced by sturdier dark-glass vessels in rounded forms by 1650. So-called “shaft and globe” shape vessels evolved to more “onion” shapes and, in the 1700s, to cylindrical forms. These eventually became the shapes we recognize as generic wine bottles today. The sides of some specially commissioned bottles had applied and stamped “seals” with the initials, names, or crests of owners or taverns as well as names of the beverages.

Although wine bottles continued to appear on dinner and drinking tables, from the late 1600s onward fashionable hosts increasingly decanted their wine in elegant, usually colorless glass vessels. In the 1700s English and continental European glass production innovations made decanters available to a broader market, and Americans began competing on some scale in the early 1800s. Some decanters were made in graduated sets, from half-pint to two-quart size, often with accompanying tumblers and wineglasses.

Related Themes: