Since ancient times, grape bunches and grapevines have been associated with wine-rich celebrations. In some cases, such motifs reflect religious beliefs or practices. Jewish blessings over the wine during Sabbath prayers give thanks for “the fruit of the vine,” and grapes are found on both Jewish and Christian religious objects. More often, however, such ornament is associated with secular activities and, when used allegorically, seems to refer to Plenty. On neoclassical objects and architecture from the late 1700s onward, grapevines were often arranged in meandering bands or border motifs.

Since ancient times, grape bunches and grapevines have been associated with wine-rich celebrations. In some cases, such motifs reflect religious beliefs or practices. Jewish blessings over the wine during Sabbath prayers give thanks for “the fruit of the vine,” and grapes are found on both Jewish and Christian religious objects. More often, however, such ornament is associated with secular activities and, when used allegorically, seems to refer to Plenty. On neoclassical objects and architecture from the late 1700s onward, grapevines were often arranged in meandering bands or border motifs.

Grapes and grapevines have also been associated with the passage of time. In neoclassical portrayals of the seasons, Bacchus represents Autumn and is often bedecked in grapes, holding a wineglass. Grape harvesters are also symbolic of this time of the year.

Dish with border samples

Dish with border samples

Davenport factory

Longport, Staffordshire, England; 1809–16

Earthenware (creamware)

Inscribed “Joseph Allen Crocker. /China, Glass & / Earthen-Ware, Dealer; /Boston.”

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1965.1429

This sample dish includes a grapevine border, among others, that would have been available to consumers who ordered Davenport creamware from Boston merchant Joseph Allen Crocker. Crocker’s Boston Gazette advertisements featured a broad range of fashionable ceramics and glass, including many drinking vessels.

Pitcher or ewer

Pitcher or ewer

Edward Lownes

Philadelphia,Pennsylvania; 1827

Silver

Inscribed “Presented / to / Dr. Philip Syng Physick / As an acknowledgement of the services and / in testimony of the affection of his friend / Robert Wharton. / March 6th.. 1827.”

Museum purchase 2000.26

Dr. Philip Syng Physick, grandson of Philadelphia silversmith Philip Syng Jr. and the father of American surgery, was rewarded by some of his patients with presentation silver. The grapes on this pitcher indicate that it was appropriate for wine. Evidence for such usage includes Wedgwood jasper stoneware made from 1775 onward in the forms of paired “wine and water” jugs ornamented with grapes for wine and seaweed for water.

“Fox & Grapes” gasolier

Cornelius and Company

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1840–60

Brass, glass, iron

Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle and Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Hennage 1993.71

The fable entitled “The Fox and the Grapes” is among the most enduring passed down to us from Aesop, who is thought to have lived on the island of Thrace in the 6th century BC. In the tale, a fox sees a vine with tasty-looking grapes hanging just out of reach. When, after several attempts, he cannot get to the fruit, he decides that the grapes are actually sour and not so tasty looking after all. The moral? A wise person doesn’t want what he can’t have. On this elegant gasolier, the fable is portrayed in pierced relief in the spaces between the arms.

Tobacco pipes

Europe; 1800–1850

Earthenware

Museum purchase with funds provided by Henry Francis du Pont 1959.4.22, .21

The small size of these grape-bunch pipes may indicate they were intended for women.

“Toby Fillpot” pitcher

W. T. Copeland & Sons, Ltd.

Staffordshire,England; 1890–94

Stoneware

Museum purchase 2005.516

Boldly modeled grapevines combined with a figure raising a foaming jug, on one side of this vessel, indicate it was intended for both wine and beer. The scene can also be found printed on  creamware, with the upraised vessel inscribed“Toby Fillpot.” It originated as a drawing byRobert Dighton, first published(London, 1786) by Carrington Bowles as “Toby Fillpot–a thirsty old soul.” According to a rhyme, Fillpot died of overdrinking and smoking. The figure on the second side of the pitcher is known as “The Smoker.”

creamware, with the upraised vessel inscribed“Toby Fillpot.” It originated as a drawing byRobert Dighton, first published(London, 1786) by Carrington Bowles as “Toby Fillpot–a thirsty old soul.” According to a rhyme, Fillpot died of overdrinking and smoking. The figure on the second side of the pitcher is known as “The Smoker.”

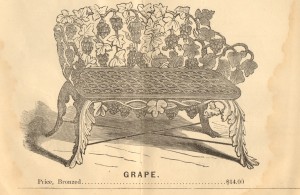

Garden chair

Garden chair

England or United States; 1860–70

Iron

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.4213

The grapevine chair has been partially restored to show some of its original green paint. Early 20th-century owners like Henry Francis du Pont sometimes coated cast iron garden furniture with linseed oil, thinking that it would protect it from the elements. Over time, as can be seen here, this coating might blacken, crack, and crumble.

Advertisement for “John A. Winn & Co., Manufacturers” (with detail)Boston,Massachusetts; 1860–75

Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Library Col. 214 77×270.26

Nineteenth-century specialists like Winn & Co. of Boston offered numerous objects for display in the garden. Among them were cast iron chairs and benches featuring grapevines.

Marking the Time of Year

Autumn

Autumn

Richard Purcell, after Robert Pyle

London, England; 1755–65

Ink, watercolors on laid paper

Museum purchase 1959.74.11a,b

Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar is credited with creating, in 1641, the earliest set of prints portraying “The Four Seasons” as three-quarter-length, elegantly attired young women in settings expressive of the time of year. The Autumn seen here, published by Robert Sayer, features a young woman harvesting grapes.

Bacchus figures

Staffordshire, England; 1775–95

Earthenware (creamware)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.2135; Gift of Mrs. Jack L. Leon, in memory of Jack L. Leon 1983.53

Eighteenth-century English and continental European sets of classical figures representing the four seasons show Autumn as Bacchus with grapes and often a wineglass. On some fashionable dinner tables, sugar or ceramic versions of such figures were combined with marzipan, wood, moss, or colored rock to create centerpieces. Sugarwork figures tinted with saffron (for yellow) or spinach juice (for green) are thought to have inspired less-costly earthenware imitations like those shown here.

Mug with “OCTOBER” allegorical scene

Neuwelt, Bohemia (Czech Republic); 1765–80

Glass (nonlead)

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1969.1428

Enameled white glass was produced in northern Europe for many export markets, including America, and is thought to have been considered a less-costly alternative to porcelain. In addition to the name October, this mug indicates the time of year with grape harvesters and the zodiac symbol for Scorpio.

SEPTEMBER

Probably Canton, China; 1790–1810

Oil on glass, gilt

Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont 1959.764a,b

In Philadelphia as early as 1747, merchants Neat and Smith of Front Street advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette that they had newly imported views called “Seasons” and “Months of the Year” for sale. In 1754 Mathew Clarkson offered “THE four seasons, painted on glass, and mezzotinto [and] the twelve months” all “neatly framed and gilt.” Later in the century, Chinese artists working in the export trade were commissioned to reproduce such themes by “reverse-painting” the designs on glass.

Related Themes: